The MacGregor Golf Co. was founded on innovation -- on the creative process of making something new from existing resources. And through the thick and thin of a storied business history, the company has maintained that inventive genius in golf equipment design and manufacture.

The Copying Lathe & The Rise of MacGregor

It began in 1829, when the Crawford brothers founded the Dayton Shoe Last Company, in Dayton, Ohio. From shoe lasts to golf clubs? Yes, and it wasn't as circuitous or accidental a connection as one might assume. The lasts used by shoe manufacturers were made by a copying lathe, essentially the same device by which keys are today made in a hardware store. A model of the item to be copied is secured on one side of the lathe. As it turns, its contours are passed over by a stylus. A cutting tool also secured on the lathe is connected to follow the path of the stylus. In doing so, it transforms a piece of unformed material into an exact replica of the model. The copying lathe was originally invented to form irregularly shaped rifle stocks. Eventually, it was adapted for numerous other manufactured items, including shoe lasts, baseball bats, and the wooden heads for golf clubs. It began in 1829, when the Crawford brothers founded the Dayton Shoe Last Company, in Dayton, Ohio. From shoe lasts to golf clubs? Yes, and it wasn't as circuitous or accidental a connection as one might assume. The lasts used by shoe manufacturers were made by a copying lathe, essentially the same device by which keys are today made in a hardware store. A model of the item to be copied is secured on one side of the lathe. As it turns, its contours are passed over by a stylus. A cutting tool also secured on the lathe is connected to follow the path of the stylus. In doing so, it transforms a piece of unformed material into an exact replica of the model. The copying lathe was originally invented to form irregularly shaped rifle stocks. Eventually, it was adapted for numerous other manufactured items, including shoe lasts, baseball bats, and the wooden heads for golf clubs.

In the early 1880s, two Daytonians, John McGregor and Edward Canby, became major investors in the Dayton Shoe Last Company, which now became known as Crawford, McGregor and Canby. Of the two new partners, Canby was the more dynamic businessman, but McGregor had a not insignificant role in the company's move into the golf industry. A native Scot, he talked Canby into trying the game of golf, which at the time -- near the turn of the 19th century -- was practically brand new to the United States. An avid sports enthusiast, Canby liked the game. A visionary as well, he became convinced that golf would become a major sport -- and business -- in America. He soon began to play a pivotal role in those developments. To understand this, turn of events, it is necessary to understand how wooden heads for golf clubs were manufactured until the late 1800s. It was a relatively primitive, and certainly labor-intensive technique, done entirely by hand. Beginning with a hunk of wood roughly in the shape of a thick boot and called a flitch, the clubmaker, using a saw, a chisel and hammer, a file, and sandpaper, worked the flitch down into a clubhead. He then coated it with varnish, and attached a shaft to it. This laborious process produced perhaps one finished head per day, per worker. Now, the story of how this changed, and how it brought the MacGregor Golf Company into existence, becomes anecdotal. Robert White, born in St. Andrews, Scotland, was among the vanguard of his countrymen who emigrated to the United States and became its first golf professionals. He was never much of a golfer, by professional standards, but he had a long and distinguished career in American golf that included helping found the PGA of America; he was the association's first president. Incidentally, he also helped create MacGregor Golf. Golf pros of the time were jacks-of-all-trades -- they taught golf, maintained the course, made clubs. One day, in 1894, while the professional at the Myopia Hunt Club, in Massachusetts, White was in his shop laboring over a new wood clubhead. A local carpenter, named Gardner, happened by. After watching White saw, file and sweat over his creation, Gardner remarked, "There's a shoe factory over at Lynn where I could do that wood job of yours in two or three minutes." Lynn, Massachusetts was then the center of shoe manufacturing in the United States. White gave Gardner a chance to match deed to word, and said later, "The fellow did turn out some beautiful clubheads." He did, almost certainly on a copying lathe used for making shoe lasts.  Apparently, White was not moved enough by the carpenter's example to look further into how he did the work, for when he became the head professional at the Cincinnati Golf Club, in Ohio, in 1896, a similar incident seems to have occurred. This time, a member of the club saw White hacking out a wood clubhead the old-fashioned way, and told the pro the work he was up to could be done better and much easier on shoe last machinery. White could see for himself by visiting the Crawford, McGregor & Canby company, a few miles up the road in Dayton. White went to Dayton and met Edward Canby, who realized an opportunity. He could turn out wooden clubheads on his copying lathes. This would provide a source of income and keep his workforce active through the inevitable down periods in shoe manufacture, when the need for lasts slowed. Furthermore, making wooden clubheads would come easily to workers generally trained in woodworking. In addition, Canby learned from a newspaper article that some 500 golf courses were in play around the country, that $50 million was invested in the game, and that over 125,000 golfers in the country were spending an estimated $10 million per year on golf. These were intriguing numbers for an enterprising businessman like Edward Canby, and in March, 1897, Canby diversified; his company would make shoe lasts and golf clubs. Crawford, McGregor & Canby got off to a quick start as golf club manufacturers. Within the first year or two, they were turning out clubheads at a rate of up to 250 a day, thanks to the copying lathe. Such production figures immediately put the firm at the forefront of the industry as it was developing in the United States. It followed that by making golf clubs more widely accessible, and affordable, the game itself could grow. And it did, exponentially, not only for Crawford, McGregor & Canby but for other manufacturers coming into the business. But where the company really enhanced its position in the new and burgeoning American golf industry was in the use of persimmon for wooden clubheads. Hail Persimmon!

Persimmon is an Algonquin/Creek Indian word for a medium-sized tree native to the United States, which is found mainly in the American mid-south. The wood was well-suited to shoe lasts, and because the persimmon market had long been in Memphis, Tenn., making it geographically convenient to Dayton, it was used almost exclusively by the Dayton Last Works. It was the logical wood of choice for the clubheads the company began turning out. In doing so, Crawford, McGregor & Canby's golf fortunes were turned up another notch because persimmon was discovered to be far more suitable to golf than the dogwood and beech that had been used for clubs since the 1400s. Relative to persimmon, beechwood was too soft; dogwood, harder but brittle. Persimmon struck a happy medium. A member of the ebony family, it is hard enough but has an interlocking grain that resists splitting. It is also relatively light, and can therefore take lead filling and a metal sole plate without getting too heavy for golf. Persimmon is an Algonquin/Creek Indian word for a medium-sized tree native to the United States, which is found mainly in the American mid-south. The wood was well-suited to shoe lasts, and because the persimmon market had long been in Memphis, Tenn., making it geographically convenient to Dayton, it was used almost exclusively by the Dayton Last Works. It was the logical wood of choice for the clubheads the company began turning out. In doing so, Crawford, McGregor & Canby's golf fortunes were turned up another notch because persimmon was discovered to be far more suitable to golf than the dogwood and beech that had been used for clubs since the 1400s. Relative to persimmon, beechwood was too soft; dogwood, harder but brittle. Persimmon struck a happy medium. A member of the ebony family, it is hard enough but has an interlocking grain that resists splitting. It is also relatively light, and can therefore take lead filling and a metal sole plate without getting too heavy for golf.

Another advantage to persimmon is that it is relatively free of knots, which makes for less spoilage in the turning process. Also, persimmon does not contract and expand as much as other woods in hot and cold weather, an advantage in that golf is played in widely varying climatic conditions. Finally, it gives a clean and smooth look when it becomes a clubhead, as well as a certain soft feel when it strikes a golf ball. All this practical and aesthetic delineation of persimmon is effectively a nostalgic reminiscence, for the wooden clubhead has been relegated to the dustbin of golf history by the metal "wood." But back in 1900, when Crawford, McGregor & Canby was merely three years into the golf business, so prized had its persimmon heads become that it shipped 100,000 machine-turned golf heads annually to Great Britain alone. This quantity of business got CMC off very well in its new venture, and by all means established the company's persimmon woods as the benchmark of excellence. It was a position it held for some 75 years. To this day, vintage MacGregor woods are among the most prized by golf club collectors and the few remaining traditionalists who actually play with them. How MacGregor Got Its Name

There is a subtle touch of innovation in how MacGregor Golf got its name. In March 1898, Edward Canby hired Willie Dunn as his head staff professional. Dunn was the eldest member of a famous Scottish golfing family. He was reputedly the first golfing professional in America, was runner-up in the first US Open and was a builder of golf courses, including the original Shinnecock Hills Golf Club. Canby wanted Dunn's golf expertise, but he also understood the credibility value a Scots name would bring to his golf division. Dunn's name was featured prominently on the first CMC line of clubs, and in all the company's advertising. There is a subtle touch of innovation in how MacGregor Golf got its name. In March 1898, Edward Canby hired Willie Dunn as his head staff professional. Dunn was the eldest member of a famous Scottish golfing family. He was reputedly the first golfing professional in America, was runner-up in the first US Open and was a builder of golf courses, including the original Shinnecock Hills Golf Club. Canby wanted Dunn's golf expertise, but he also understood the credibility value a Scots name would bring to his golf division. Dunn's name was featured prominently on the first CMC line of clubs, and in all the company's advertising.

However, the relationship between Canby and Dunn didn't wear well, and when Dunn left the company there was the problem of keeping the firm at least nominally connected with golf s birthplace. Canby found the solution in the next office over. He obtained a trademark, "J. MacGregor," to be used on CMC clubs, which he could do because there was a person by that name with the firm--John McGregor, of course.

The interesting thing about this is how John McGregor's name came to be spelled MacGregor, in respect to its use by the company. The Gaelic word "Mac" was used originally by both Scots and Irish as a prefix to surnames.

MacGregor is to say, son of Gregor. At some point in time, though, Mac also came to be spelled Mc. This variation came to be associated mainly with the Irish. That, along with the fact that Mickey (from Michael, the Irish Patron Saint), was a common Irish name, led to the derogatory name for Irishmen: "mick." This word, slang etymologists say, originated in the United States around the mid 1800s, when there was a huge influx of working-class Irish immigrants who were treated disrespectfully by the English-rooted establishment. It is pure speculation at this late date, but it is likely that Edward Canby did not want his golf equipment to carry a name, however Scottish its owner was, that had an Irish connotation. Mac became a Scot-only prefix. Hence, McGregor became MacGregor. Oddly, the company was inconsistent in referring to itself. The J. MacGregor tradename was used on equipment beginning in 1900, but in the advertisements, it produced, the company referred to itself as Crawford, McGregor & Canby. Editors didn't help the matter. For instance, in a June 1935 issue of Golfdom magazine, a headline read: "Joyce Wethered Added to the McGregor Advisory Staff." Another newspaper headlined the news, "Joyce Wethered Joins MacGregor Golf Staff." In 1944, the confusion was eliminated. P. Goldsmith, Sons now owned the golf company, but the president of the golf division, Clarence Rickey, decreed that it would be known as MacGregor Golf. Socket Construction

Every great artist, from Michelangelo to Picasso, begins by borrowing if not outright copying from the works of previous masters. He then modifies, adapts and transforms the original until it becomes his own creation. This same process exists among manufacturers of products. To see the value of someone else's work, and make something entirely different out of it, is a talent in itself -- and MacGregor Golf was never short of it. For example, around 1898 a Scot named Scott took a patent on a wood club with the shaft inserted in a hole (socket) drilled in the neck (hosel). Until then, shafts were spliced around the outside of the neck and held in place with glue and a strong thread called whipping. Splicing was not the most secure way to attach two parts of a club at the point of greatest stress when a ball is hit, and Scott's was a huge fundamental improvement in club construction. MacGregor was first to license themanufacture of golf clubs using Scott's idea. It wasn't long before all golf clubs were made this way, with variations to bypass Scott's patent, which eventually was rendered null and void. The Insert

The first use of inserts in wooden head clubfaces came around the middle of the 19th century, with the advent of the gutta-percha ball. Until then, the golf ball was a leather bag filled with feathers. It was not much of a threat to the condition of the clubface. The solid, hard-rubber gutta-percha, however, caused nicks and dents in clubfaces, and finally just wore them out. To prevent this, someone got the idea of putting a slab of thick leather into the center of the clubface. It made manufacture costlier, but saved throwing the entire club away when it became too guttie-worn. The first use of inserts in wooden head clubfaces came around the middle of the 19th century, with the advent of the gutta-percha ball. Until then, the golf ball was a leather bag filled with feathers. It was not much of a threat to the condition of the clubface. The solid, hard-rubber gutta-percha, however, caused nicks and dents in clubfaces, and finally just wore them out. To prevent this, someone got the idea of putting a slab of thick leather into the center of the clubface. It made manufacture costlier, but saved throwing the entire club away when it became too guttie-worn.

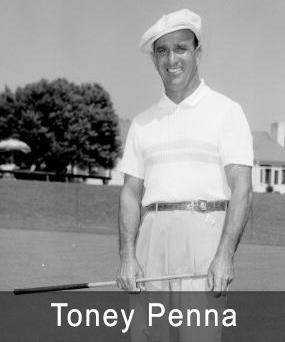

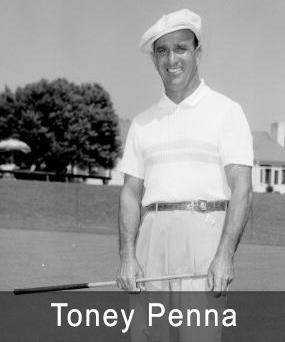

When persimmon became the material of choice for woods, the need for a protective insert declined. At around the same time the three-piece, rubber-core golf ball was introduced, which made the insert even less necessary because it had a much softer cover than the guttie. However, the insert was given a new reason for being. It was felt that an insert of the right material could give the already much peppier new golf ball an even faster sendoff, and added distance. Thus, in 1913 the company began offering clubs with a variety of insert materials -- for example, one of compressed paper. But MacGregor's insert piece de resistance was of genuine ivory. A MacGregor catalog described it as follows: "Used by Charles (Chick) Evans and many other prominent golfers, the J. MacGregor Ivory Face Clubs have made a Big Hit." Irons, by the rules of golf, could not have inserts. But the idea of something on the face of an iron to provide a "target," and to frame the ball for the golfer was in Toney Penna's mind when he created the MacGregor "Colorkrom" MT (for MacGregor Tourney) iron, in 1955. The entire scored area of the iron's face was bronze-colored. It was derided by some people as strictly cosmetic, but it did indeed give the golfer a good picture of where the club and ball were supposed to meet. It sold very well. Wood Heads Go CompactBy 1910, MacGregor was recognized as the preeminent manufacturer of wood clubs. The reputation was further enhanced when Will Sime was hired, in 1912. A Scot who had made clubs for Harry Vardon, J.H. Taylor and James Braid (the famed British Triumvirate of champions), Sime was signed on as MacGregor's chief club designer. He may have been the first in the industry to ever hold that specific title. The shape of wood heads for almost as long as golf had been played was long-nosed. They looked much like a hockey stick, not surprising in that the origins of the game have been traced to a form of hockey played by the Dutch. This shape, called "long nose," was gradually being transformed, and Sime completed the transition with a shape inspired by the shape of a biscuit his mother baked, called a bap, which was blocky in configuration. The idea behind Sime's MacGregor "Bap" driver and brassie was that a more compact head could deliver a more solid and powerful blow. The "Bap" was introduced in 1921, and proved extremely successful. For 15 years it was the best selling wood in the MacGregor line, and owing to this success the rest of industry developed similarly shaped heads. The MacGregor "Bap" effectively revised the basic design of the wooden clubhead. The First Coming of Steel

The most substantive and influential development in golf equipment in this century, after the invention of the three-piece golf ball, was the introduction of the steel shaft. MacGregor was the first to use it in its equipment, and was thereby an integral part of the revolution it caused in equipment and how the game was played. The most substantive and influential development in golf equipment in this century, after the invention of the three-piece golf ball, was the introduction of the steel shaft. MacGregor was the first to use it in its equipment, and was thereby an integral part of the revolution it caused in equipment and how the game was played.

The first known steel shaft appeared in Scotland in 1893, brought out by a blacksmith named Thomas Horsburgh. It didn't catch on, probably because it was a solid piece of steel and too heavy for golf. United States patents for two other steel shafts were issued between 1910 and 1915, one to A. F. Knight, the other to Allan Lard. These were hollow tubes, therefore relatively light. Lard's version was perforated, to reduce torque. Neither caught anyone's fancy, if only because golf's two main ruling bodies, the USGA and the R&A, would not allow them to be used in its competitions. (Only hickory was allowed.) Nonetheless, in the early 192Os, the British company, Apollo, introduced and marketed the first viable steel shaft. This shaft didn't appear in the United States at the time. However, during this period, the Bristol Steel Co., in Connecticut, also developed a sound, tubular steel shaft. What made it eventually successful was that whereas the Knight, Lard and Apollo shafts were tubes with an overlap, Bristol found a way to weld a seamless tube. This made it more consistent in its performance, and more attractive to the eye. Getting the steel shaft "legalized" by the sanctioning bodies was a problem put in the hands of Harry Lagerblade, a club professional hired by Bristol to head up its steel shaft division. Lagerblade was aware of animosity toward the USGA held by the Chicago-based Western Golf Association (WGA). The WGA, founded at almost the same time as the USGA, felt the USGA was an elitist east coast group that shouldn't serve as the Game's central ruling body. Lagerblade thought the WGA might be interested in recognizing the steel shaft, if only to tweak the USGA, and arranged a test of it at WGA headquarters. On a cold and windy day in May, 1922, at the Edgewater Country Club, Chicagoan Charles "Chick" Evans, the great amateur champion, and two highly regarded professionals, Jock Hutchison and Laurie Ayton, hit balls with both hickory and steel shafts. In attendance was WGA president Albert Gates. The players found the steel quite acceptable, as did Gates. A newspaper account of the test also made an argument for the coming of steel, noting that it was more uniform and durable than hickory, cheaper to buy, and that with the growing popularity of golf, some 5,000,000 feet of hickory was used annually for golf clubs. In short, the hickory supply was becoming limited. This was also noted by George Mattern, the MacGregor plant manager, who was at the test site. Mattern was quoted as saying that while his firm was able to get all the hickory it wanted, it had been forced to reach out farther into the available supplies and figured that 75 percent of the usable hickory had been exhausted. For economic and supply reasons alone, steel shafts were becoming more viable, and Albert Gates announced that the WGA would permit their use in its tournaments -- which were consequential. The Western Open was at the time considered a "major" title, and the Western Amateur was on the same level on the simon-pure side of the game. Lagerblade's ploy worked. Not long after the WGA approved steel, the USGA said it would reconsider its ban, and in January, 1924 finally sanctioned steel shafts. But the Bristol company -- and MacGregor -- did not wait for the USGA to get off its high horse. Bristol began turning out its shafts in 1922, and MacGregor was its first big customer. A Bristol ad in the May, 1922 issue of Golf Illustrated magazine said: "Golf Clubs fitted with Bristol Steel Shafts can now be supplied by the Crawford, McGregor & Canby Co., of Dayton, Ohio, and the (much smaller and younger) Hillerich & Bradsby Co.,of Louisville, Ky." As an example of how steel shafts drove down the cost of a quality golf club to the average golfer, and thereby made the game all the more accessible to the masses, a 1923 MacGregor catalog offered its BB Six Spot Ivory Face Brass Back Drivers and Brassies with steel shafts for $6.25 wholesale, and for $8.25 with hickory shafts.  Protecting Steel Protecting SteelThe first steel shafts were basically uncoated and subject to rusting. What's more, many golfers were still fond of hickory and complained that cold hard steel didn't look as good as hickory, and also caused a lot of shock vibration in their hands. MacGregor found a way to keep the steel from rusting, and dampen the shock. It developed a celluloid tradenamed "Macoid" which looked something like wood, and helped prevent rusting. Spalding would use a similar coating, in tan, on its first Bobby Jones Signature irons and woods, introduced in 1930. It wasn't until the auto industry found a way to make chrome adhere to steel for car bumpers that the rusting problem was completely solved for the golf equipment industry. That chroming process found its way into the manufacture of iron clubheads, and MacGregor was probably the first to produce chrome-plated irons when it introduced the "Radite No-Rust" iron, in the late 1930’s. Dampening SteelThe other complaint about steel, the shock or vibration factor, went beyond mere aesthetics. Steel didn't have the nice soft feel of hickory, and on mis-hits in particular could be painful for those who played and practiced a lot. MacGregor was the first to counter the vibration problem with its "Neutralizer," a wooden dowel of tough spring hickory inserted in the shaft where it joins the lubhead. It absorbed shock and vibration, while also strengthening the neck of the club. Other clubmakers would devise shock absorbers of their own design. Testing, Testing

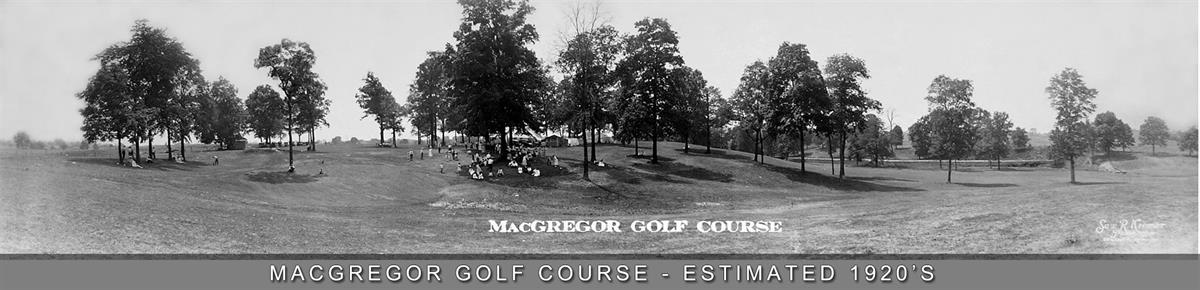

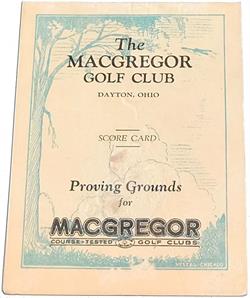

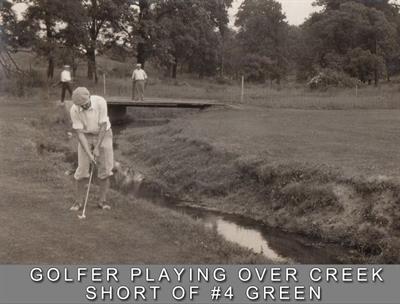

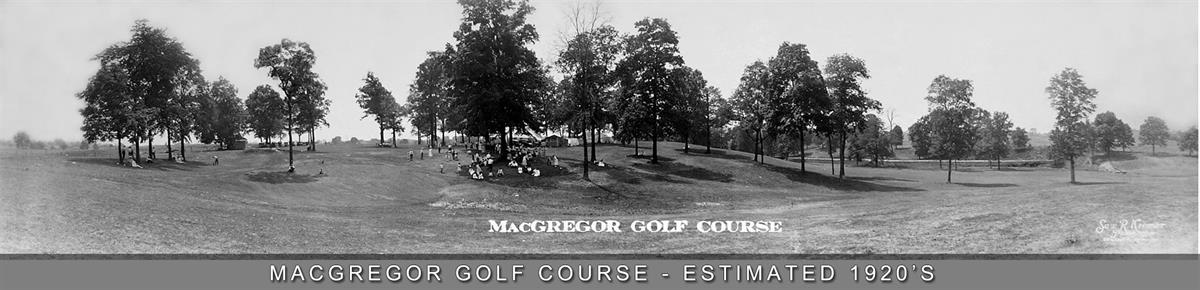

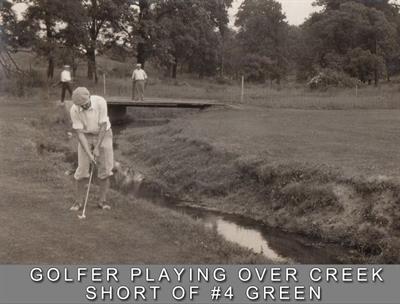

By the late 1920s, Edward Canby, now age 70, had such a good feeling of well-being and was so optimistic about MacGregor's business future that built a 9-hole golf course on company property. The first known company golf course. it was excellent for employee morale, as they could play for next to nothing. But the course also gave MacGregor a very sound selling point in that the people who made MacGregor equipment could try out new ideas in their own "backyard!" And they did. In its advertisements, MacGregor claimed rightfully that its equipment was "course-tested." Indeed, the MacGregor golf course in this respect preempted the test facilities of other companies by some 65 years. Hard Times Breeds the Best of Times

For all its success through the 1920s, when the Great Depression hit in 1929-30, MacGregor began to have its own hard time. By 1932 its workforce was halved, and those who did keep their jobs came in only two or three days a week. Indeed, by the beginning of 1934 the specter of bankruptcy was looming over MacGregor. For all its success through the 1920s, when the Great Depression hit in 1929-30, MacGregor began to have its own hard time. By 1932 its workforce was halved, and those who did keep their jobs came in only two or three days a week. Indeed, by the beginning of 1934 the specter of bankruptcy was looming over MacGregor.

Although a well-established and profitable company, it did not have the diversification of its arch rivals, Spalding, and the newer but growing Wilson Co. The latter two made equipment for a variety of games, whereas MacGregor was only a golf company. Basketball, baseball, and football were far more economically accessible to a strapped populace than golf. Furthermore, MacGregor had not established itself as a golf ball manufacturer, whereas Spalding had long dominated this end of the business and Wilson was gaining ground. People could do without a new set of clubs, or make do with what they had, but balls, which didn't cost all that much in the first place, were regularly lost or beat up. Spalding and Wilson could count on getting business whenever golf balls were sold. At the same time, Edward Canby, who had become MacGregor's controlling stockholder and chief operating officer, was at an age (80) when he could no longer handle the day-to-day stress of running a large business. With neither his son or grandson suited to take over the concern, and facing the prospect of simply closing a business he had proudly grew to prominence, Canby called in a Cleveland management consulting firm, Robert Heller, Inc., to put MacGregor in shape for sale. This last-ditch effort proved to be one of the most providential decisions Canby ever made vis-a-vis MacGregor Golf. Robert Heller, Inc. assigned Clarence Rickey to the MacGregor project. Rickey's father was a cousin of Branch Rickey, the progressive major-league baseball executive who broke the color barrier when he signed Jackie Robinson to play for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Clarence was himself an athlete, earning a football scholarship to Northwestern University. After military service in World War I, he played professional baseball and eventually became a sporting goods salesman. A physically imposing man with a quick mind, and what Byron Nelson would describe as a "flamboyant" personality, Rickey took on the MacGregor job with gusto and a clever business sense. He decided that MacGregor was still a premier name among golf consumers, had the best bench trained clubmakers in the industry, and with some fresh approaches could come back to prosperity. Not long after Rickey arrived on the scene. Edward Canby died. This forced the issue of selling the company. Two firms bid for it, Wilson and P. Goldsmith and Sons. Rickey recommended Goldsmith, feeling that Wilson would simply dissolve MacGregor and eliminate a major competitor. Goldsmith was a full-range sporting goods manufacturer that had tried unsuccessfully to get into golf, and felt this would be the best way. Goldsmith got the prize, with the proviso that Rickey stay on as president. The deal was done in 1936. Going after the "Carriage Trade"Rickey's main plan was to identify MacGregor as golf's quality house, which meant courting a pro-shop-only trade. While Rickey wouldn't ignore the retail stores in city downtowns, he left the bulk of that business to Wilson and Spalding and went for the moneyed members of private clubs. This was where most pro shops were located at the time. Hence, the "carriage trade."  The Armour & Penna Connection The Armour & Penna ConnectionThe first step in implementing the pro-shop only policy was to bring to MacGregor a high-profile professional. The choice was Tommy Armour, who qualified in a number of ways. Armour was a champion player and winner of the US and British Opens, the PGA Championship, three Canadian Opens, and a Western Open. This gave him absolute golf credibility among the club pros that the company would be attempting to seduce. Furthermore, Armour was well-educated -- he was a graduate of Edinburgh University and had an aristocratic bearing, dressed with quiet good taste, and had a resonant voice and the speaking, style of a dramatic factor. Perfect for courting the carriage trade. Armour's Irons . . . and WoodsIn later years. many thought Tommy Armour was little more than an up-front man for MacGregor, that he made no real contribution to the design of the clubs under his name. That was not at all the case. Armour not only brought his sense of style to MacGregor clubs, he also added a significant technical advance. Armour didn't like the bulkiness of the "Bap" woods. He wanted the clubs to "flow," as he put it, and he had the "Bap's" sharp edges rounded, and the top of the clubhead slightly crowned. It became the classic MacGregor wood that would entrance golfers then, and does to this day with its beauty. Bulge & Roll

But Armour also added a functional element to the new woods he helped design. The "Bap" had a bulged face, a convex curve from the top line to the bottom line. Armour added a convex curve from the toe to the heel. He got the idea from an engineer friend who was the director of the Illinois Institute of Technology, in Chicago. The bulge had been part of clubface construction for many years, the roll was something new and different. The combination of bulge and roll formed a 10 to 11 degree point at the center of the clubface, the sweetspot. The point provided a livelier send-off of the ball. Furthermore, on off-center hits the roll acted to minimize or correct to some extent a slice or hook by what is known as the gear effect. The result was MacGregor's "4-Way Roll" wood, which was both a huge financial success and an important advance in golf club design and technology.

Toney Penna's Input

Toney Penna was a kind of antidote to Tommy Armour's slightly regal manner with the club pros. A tough little man who emigrated to the United States from Italy when he was a pre-teen, and remembered well how it was in the bottom of the "banana boat" that brought him over, Penna was a pro's pro. He got into golf as a caddie, learned clubmaking from an early American master, Cuthbert Butchart, worked as an assistant to the legendary "Wild Bill" Mehlhorn, and became a fine tour pro with an excellent and much-admired golf swing. He was also a restless, firebrand personality, a classic case of the minority immigrant out to make good in America.

Rickey hired Penna to travel the country calling on club pros, not so much to take orders (although he would) but to sell MacGregor as the company through which they could make a good buck. Penna's other charge was to play tour events from time to time, and otherwise hang around the circuit and scout players to sign on as MacGregor staff players. The club pros were impressed with Penna's knowledge and ability to play; the tour pros were impressed by his ability, his knowledge of the golf swing, and his free-spending ways. Rickey put $ 10,000 in a special account for Penna to draw on, and when it was used up he put in another $10,000. Penna never filled out an expense report in his entire career with the company. He drove big cars very fast, talked police out of speeding tickets with a dozen golf balls, stayed in the best hotels, and, with his bright smile and energy, signed one of the most impressive tour pro staffs the game has ever had.

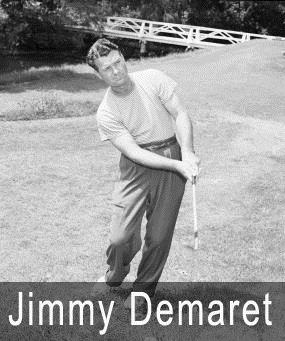

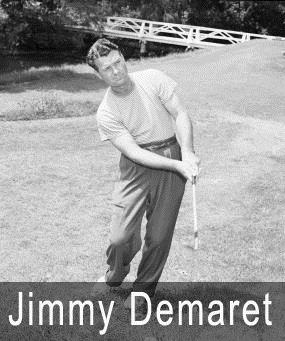

The Fabled MacGregor Tour Staff Takes ShapePenna's first catch was Jimmy Demaret, who was the same age as Penna, and also liked to dress well and live the high life. Rickey had his doubts about signing Demaret, a Texan, because Rickey didn't think he could influence the eastern and midwest markets. So one evening in a nightclub in Birmingham, Michigan, where the 1937 US Open was being played, Penna had his boss meet Demaret. At one point in the evening, Demaret got up to sing a few songs with the Wayne King Orchestra, demonstrating not only a pleasant voice, but a winning personality. Rickey was sold.

Next up was Byron Nelson. Here, Penna got a little lucky. Nelson had been with Spalding for a couple of years when it changed its tour pro program, putting together a cross-country exhibition tour featuring four star players-Jimmy Thomson, Lawson Little, Harry  Cooper, and Horton Smith -- and releasing the rest of its staff. Cooper, and Horton Smith -- and releasing the rest of its staff.

"That was in 1939", Nelson recalled. "Toney Penna and Tommy Armour had a lot to do with my signing with MacGregor. I signed the contract on June 1, 1939, picked out a set of MacGregor clubs from Armour's shop in Boca Raton, and two weeks later used them to win the US Open." Shortly after signing Nelson, Penna got Ben Hogan's signature on a MacGregor contract. This seemed chancy at the time, as Hogan was still fighting a wild hook that kept him from realizing his true potential. "It was in Florida," Penna remembered. "Hogan was nearly broke, and needed to get to Pinehurst for the North & South. I had $500 on me, but offered him $250 in case he wanted more. He took the two-fifty, and won the North & South. It was his first solo victory as a pro." The total outlay for signing Demaret, Nelson and Hogan to play MacGregor equipment was $5,000. It was, in retrospect, one of the greatest bargains of its kind in golf history. However, MacGregor did have a bonus program, and it cost. "I got an extra thousand for winning the US Open," said Nelson, "and we got maybe three or four hundred for winning an LA Open or other tournaments that were not majors but were notable. I believe when I won the US Open it was the first major title by a MacGregor player in 24 years." After Nelson broke the drought, there was a deluge. In major championships between 1937 and 1959, MacGregor players won 10 PGA Championships, nine Masters, eight US Opens, and one British Open. Also in that time frame, ten MacGregor players were leading money winners on the year, and eight were Vardon Trophy winners. Besides Hogan, Nelson and Demaret, the MacGregor staff included Craig Wood, Lew Worsham, Jim Tumesa, Doug Ford, Jackie Burke, Jr., Lionel and Jay Hebert, Bob Rosburg, Herman Barron, Ted Kroll, Bob Toski, George Baver, Mike Souchak, Frank Stranahan, Marlene Haiacre, Beverly Hanson, Louise Suggs, Mickey Wright, among many others. Taking Orders

While Penna was creating his fabulous staff of tour pros, Clarence Rickey put together an all-star sales force. He made sure his men were good golfers, and thereby able to gain the respect of the club pros. Two in particular were Tom Robbins and Harry Adams. Robbins took up golf at age 30, played in seven USGA Senior Amateur Championships, and won it once, in 1958, at age 65. Adams wasn't quite up to Robbins' as a player, but he was a good stick and a garrulous sort who got everyone's respect. They and their kind made the pro-only policy work, and MacGregor rose something like a phoenix from the ashes of the Depression. All the while, it kept up its innovative clubmaking.

The Broaching Machine

Hugo Goldsmith was president of MacGregor during the most fertile years of its association with P. Goldsmith Sons. Hugo had an inventive way with machinery. He had devised a machine for automatically winding baseballs faster and more economically, and adapted the machine to winding golf balls when MacGregor began producing its own ball. But the machine Hugo Goldsmith developed that had the most impact on club production was his broacher. Until this was implemented, all golf companies had to buy different forgings for every model of club it produced -- one for raised-back irons, another for a plain-backed iron, and so on. With five or six models per season, and nine or ten different heads for each model, it was a high-cost inventory and production nightmare. Goldsmith's idea was to have a basic forging with a flat back and an extra amount of metal that could be broached into a variety of back designs. The only problem was, no such broaching machine existed. Hugo approached the Cincinnati Milling Co. with his idea, and after three years of work it designed a hydraulically operated broaching machine. It was so big that when it was delivered to MacGregor, in 1946, a wall of the factory had to be removed to get it in. This machine could only cut or shave on a straight line, and another milling machine followed that could cut on a contour. Both saved money, and just as importantly, they gave the club designer a far wider latitude than ever before for back-design conceptions. But more than design features came out of it. The broaching machine allowed Toney Penna to create the first lower-center-of-gravity iron, the famous MT.  The MT Iron Introduces L.C.G. The MT Iron Introduces L.C.G.By the early 1950s, Toney Penna had risen to chief designer for MacGregor. His first big hit was the MT iron, which was a radical departure in two ways. One, it had an extremely small head, and was especially shallow from top to bottom. The compactness of the blade was accentuated by an unusually wide top line. The second departure turned out to be a far-reaching technological advance. Thanks to Hugo Goldsmith's broaching machines, Penna broached the back of the MT in such a way as to distribute the weight in a kind of delta-shaped plateau. The widest portion was directly behind and slightly below the very center of the clubface. Thus, the center of gravity (L.C.G.) was lowered, which helped get the ball airborne. With this innovation, Penna and MacGregor were some 20 years ahead of the times. The ball went farther with the MT, in part because of where the weight was concentrated on the back of the head, in part because of the height LCG gave it, and also because Penna put a degree less loft on each club in the set. The MT six-iron had 34 degrees of loft, the Armour six-iron 35 degrees. The lesser loft could be accommodated and golfers could still get proper trajectory, because of the lower center of gravity. Here again, Penna and MacGregor predated by some 20 years what would become a common practice in golf club manufacture. The size of the MT iron's hand made all other irons, including the Armour models, look like shovels. No one liked the size very much, especially the staff pros, and after one year it got a little bigger. But right from the start, the MT iron sold like wild fire. Said Leon Nelson, a MacGregor executive at the time, "I never saw orders come in so fast in all my life. I remember seeing orders from a single pro for fifty and seventy-five sets at a time. That was just unprecedented." Color Schemes

Penna's enormous success with the MT placed a burden upon him. He was expected to come up with something new, and of course successful, at least every two years, and so got busy. Penna had a special affinity with color, and this would be a feature of many of his designs. He introduced the "Colorkrom" iron, mentioned earlier. In 1959, he created an even more dramatic frame for iron faces, the Flame Ceramic black-faced FC-4000. It grew out of the nascent jet and rocket engine industry, where metals needed protection against intensely high temperatures. A process of applying ceramic powder to metal had been developed, and MacGregor adapted it for its clubs. It was an early instance of the co-mingling of golf and high-tech aeronautics that has become almost standard practice today. Penna's enormous success with the MT placed a burden upon him. He was expected to come up with something new, and of course successful, at least every two years, and so got busy. Penna had a special affinity with color, and this would be a feature of many of his designs. He introduced the "Colorkrom" iron, mentioned earlier. In 1959, he created an even more dramatic frame for iron faces, the Flame Ceramic black-faced FC-4000. It grew out of the nascent jet and rocket engine industry, where metals needed protection against intensely high temperatures. A process of applying ceramic powder to metal had been developed, and MacGregor adapted it for its clubs. It was an early instance of the co-mingling of golf and high-tech aeronautics that has become almost standard practice today.

But Penna didn't stop only at coloring clubs. He more or less revolutionized the golf bag, which had traditionally been a drab brown or black leather. Bob Rickey, the son of Clarence, who became a marketing chief and president at MacGregor, amplifies: "One day, Toney made a trip through our athletic goods plant and saw them making football uniforms of nylon and jockey silk in extremely bright colors. The minute he saw those colors he had three staff bags made up, one in royal blue for himself, one in pastel green for Louise Suggs, and one in the loudest red for Jimmy Demaret, of course. The bags caused a sensation at tour events. The materials used proved impractical for golf bags, but the idea of color was established." Penna's "Eye-O-Matic" insert on woods was another interesting and somewhat pioneering use of color. It was a two-tone fiber insert, red with a white or black horizontal strip running through the center. Again, the idea was to frame the sweetspot. The Double-Duty Wedge

Being a fine and serious golfer himself, Penna also brought out clubs with improved playability factors. One very successful product was the "Double-Duty" wedge. It had a shallow groove down the center of the sole so it could be used with equal facility out of sand and off grass. It became especially popular when Lew Worsham used it to hole a 102-yard shot for an eagle two to win the 1953 Tam O'Shanter "World Open," in Chicago, and the first prize of $25,000. The shot was seen on television by millions because this was the first golf tournament to be seen on national television. Good timing. The wedge is now in the USGA Museum.

How to Court Your Customers

The Goldsmiths had a paternalistic, family-style way of operating their company, and handling their customers. It didn't have the cold, efficient character of many large corporations. As Leon Nelson recalled, "We were brought up at MacGregor to think that the club pro was king. Bob Rickey would write two-page letters to obscure pros in tank towns, which flattered them terrifically. They were not paid much attention, didn't make a lot of money, many weren't very well educated, and to get a two-page letter from the president of MacGregor asking how things were going, if they needed anything, if the family was okay, that was quite a thing. Of course, when they sold the odd set of clubs we hoped they would push us."

Nelson might also have mentioned that Bob Rickey went out of his way to find club jobs for pros who couldn't make it on the tour, were victims of racism or were otherwise down on their luck. When Charlie Sifford, Ted Rhodes, Bill Spiller and other black pros needed some clubs and were short of cash as they struggled to break down the race barrier on the tour, Rickey fixed them up with what they needed, no charge. As result of all the above, by the mid-1950s MacGregor could claim nearly 30 percent of the pro-only country club market. To indicate the value of that position, in 1956 the US Dept. of Commerce reported there were 2,996 private golf clubs in the country. With an average membership of-300, MacGregor had over 30 percent of the business of close to 900,000 golfers who were paying top dollar for equipment with the best profit margin.  The Ball Debacle The Ball DebacleMacGregor was offering a golf ball under its name before World War II, and it did well against the competition, although Spalding, Dunlop, Wilson and Acushnet were still the more dominant. However, the ball was being made for MacGregor by the Worthington Company, an Ohio-based specialist in golf ball manufacture that made them for many other companies. Hogan, Demaret, Nelson, and the rest of the MacGregor staff played the ball on tour. But Hugo Goldsmith decided it was time for MacGregor to actually make its own ball. After all, it made baseballs for the major leagues, why not a golf ball? It turned out to be a disaster. The first plant manager in the new ball department, unbeknownst to anyone, happened to be a heavy drinker, and mistakes were made with the first batch to market. In an extremely competitive end of the golf market, the first impression could not be overcome, even when MacGregor eventually began producing a good ball. In the interim, the staff tour pros were allowed to use any ball they chose until the MacGregor ball was up to snuff. When it was felt to be, Ben Hogan, who was the biggest star on the staff and very influential with the other pros in regard to quality equipment, was invited to Cincinnati to observe the testing of the ball. The results led to a classic episode in the Hogan legend, and also an unfortunate turn of events for MacGregor. Hogan spent three days in Cincinnati in early June 1953 witnessing every conceivable test of the new top-of-the-line MacGregor Tourney ball. A mechanical driving machine cranked out one shot after another. There are three versions of what happened next. Bob Rickey recalled that the haracteristically taciturn Hogan watched all the tests without saying a word. Then, on the last day, A.G. "Tony" Koegel, president of MacGregor, asked Hogan if he had seen conclusive proof that the new ball was good enough to use in the upcoming US Open. "The driving machine should have proven this, conclusively," Koegel said. To which Hogan replied, "I suggest you enter the driving machine in the US Open." He then left for Pittsburgh, and won the US Open using another manufacturer's ball. Leon Nelson said that the tests proved the ball went far enough, but that it wavered in flight. At least it did as Hogan saw it, for his comment before leaving for Pittsburgh was, "I can hit it straighter than that machine." Toney Penna suggested that Hogan had his mind made up even before he went to Cincinnati. "At the time," Penna recalled, "Hogan was playing the Titleist. So, we put a Titleist marking, on a Tourney ball, a Tourney marking on a Titleist, and gave them to Ben to hit. Only, a few of us knew this. Of course, Ben didn't. He thought the ball marked Titleist was the better one." Hogan's refusal to use the MacGregor ball finally became unacceptable to the company, especially because Jackie Burke, Jr. used it in winning the 1952 Vardon Trophy with a 70.54 stroke average. More intense pressure was put on Hogan, who responded by resigning from MacGregor. Did Hogan do this because the ball wasn't up to his standards, or because he wanted a way out to found his own equipment company, which he did the following year? No one will ever know the answer to that question, but it was clear at that time that his leaving MacGregor and impugning the quality of its product didn't help. Indeed, other staff members also decided the ball wasn't any good, and when they wouldn't comply with the company's "Play-It-Or-Else" edict, they also left. In 1957, Jimmy Demaret, Doug Ford and Dow Finsterwald were released from their contracts with MacGregor. Others would follow. Although it wasn't apparent at the time, the ball debacle signaled the end of the "new" MacGregor that Clarence Rickey had put together. But it wasn't only the ball issue. The clubs and bags continued to sell well even after the pro stars left, but now there were other forces on the loose. The business climate was being affected by the "Go-Go Fifties," a time of fast-paced, adventurous, some would say reckless stock market dealing for large stakes, and some rakish corporate mergers and diversifications led by freewheeling entrepreneurs. MacGregor, on the other hand, was still a privately-held company run by the family that owned it, and was having trouble keeping up. What's more, the blood family that owned MacGregor was running out. Hugo Goldsmith died in 1954, and there was no one among his heirs who wanted, or were considered able, to take over. The upshot was that the company was sold to the Brunswick-Balke-Coliender Co., of Chicago, a successful manufacturer of bowling equipment. The transaction took place in 1958.

When P. Goldsmith bought MacGregor, the golf company was doing around $100,000 in sales. When it sold out to Brunswick 22 years later, for approximately $5 million, it had just completed a year when it did $17 million in sales and showed a profit of $4 million. The Hard Times of MacGregor

Brunswick-Balke-Collender was headed up by Ted Bensinger, who earlier had brought his company back from near total collapse to a spectacular success. With great self-confidence, and a penchant for growth through acquisition that was in keeping with the 50's and 60's business mentality, Bensinger went on a buying spree. He took Brunswick into school equipment, hospital supplies, surgical and laboratory equipment, pleasure boats, a fishing rod manufacture, a hardware chain, and now a golf company. The latter was just one of many new ventures. As it happened, Bensinger seemed to have no special interest in golf. What's more, he applied Harvard Business School management theories to his operation, which were in essence contrary to the informal style of MacGregor. The yellow pads of MacGregor's production manager -- to keep track of things -- was replaced by an IBM computer. Research and development meetings that included club grinders and buffers as well as designers and plant managers, gave way to meetings between only certified engineers and corporate officers. That aside, the executives, dressed in fine suits, stepped out of chauffeur-driven limousines and decorated their offices with plush carpeting and fancy furniture -- all this in view of a workforce that had struggled through the Depression, and understood that equipment manufacture was a hard buck. Morale began to deteriorate in the plant, and quality began to fall. Brunswick-Balke-Collender was headed up by Ted Bensinger, who earlier had brought his company back from near total collapse to a spectacular success. With great self-confidence, and a penchant for growth through acquisition that was in keeping with the 50's and 60's business mentality, Bensinger went on a buying spree. He took Brunswick into school equipment, hospital supplies, surgical and laboratory equipment, pleasure boats, a fishing rod manufacture, a hardware chain, and now a golf company. The latter was just one of many new ventures. As it happened, Bensinger seemed to have no special interest in golf. What's more, he applied Harvard Business School management theories to his operation, which were in essence contrary to the informal style of MacGregor. The yellow pads of MacGregor's production manager -- to keep track of things -- was replaced by an IBM computer. Research and development meetings that included club grinders and buffers as well as designers and plant managers, gave way to meetings between only certified engineers and corporate officers. That aside, the executives, dressed in fine suits, stepped out of chauffeur-driven limousines and decorated their offices with plush carpeting and fancy furniture -- all this in view of a workforce that had struggled through the Depression, and understood that equipment manufacture was a hard buck. Morale began to deteriorate in the plant, and quality began to fall.

What's more, Bensinger determined that MacGregor's stance with the club pros was so sound he could make a bigger effort in the retail market. Instead, this served to alienate the club pros, who were used to getting attention paid them, good service, and no competition from retail outlets. On top of all that, the plant was moved out of Cincinnati to Albany, Georgia. The move was not to avoid labor union pressure—there had been only one strike at MacGregor in 50 years--it was to get cheaper labor, and more space. However, unlike the move from Dayton to Cincinnati, in which only a small number of workers and managers stayed back, the move to Albany cost MacGregor an entire on-the-floor workforce, and many experienced foremen and supervisors who could train the new people. A few experts did make the move to Albany--the legendary grinder Art Emerson, Jack Wulkotte, who later became Jack Nicklaus' personal club maker and repair man, Jack Hesse--and the quality of the product did not suffer disastrously. But there was a lot of turmoil within, and without. The golf industry in general was going through some watershed changes, and MacGregor's own disorder didn't help the firm though these times.  Getting Jack Getting JackAs Toney Penna got busier and busier with club design, his player scouting activities were reduced. The slack was picked up by Leon Nelson, a soft-spoken Virginian and a fine golfer, who had been a stockbroker before joining MacGregor in 1945. Nelson became something of an underground legend in the golf industry. He had considerable technical knowledge of equipment, and the ability to articulate it; he was a good golfer himself, and had a confident but unobtrusive manner. All of which engendered confidence in him, among pros as well as young amateurs with a future in the game. Young amateurs such as Jack Nicklaus. Nelson began tracking Nicklaus when he was a 15-year old Ohio high school phenom. He recalled, "Jack would come down to Cincinnati from Columbus fairly often. He liked to do a little gambling across the river, in Covington, and I would take him around the plant. We would always go over the new clubs, and select things he liked. I always thought it was interesting that when he was an amateur, Jack got a completely new set of clubs every year, and just discarded the old ones, didn't keep the driver or wedge, even. After he turned pro, though, you could hardly get him to change anything. I had to be prepared, though. He broke a lot of drivers, split them right down the face, so I always kept six of them in reserve. "I always saw something special in him, although I can hardly say I was the only one," Nelson continued. "I stayed around him a lot, and his dad Charlie. I said to Charlie once, in '56, 'Look, it may never happen, but if Jack ever turns pro give me the first crack at him'; Jack had always played MacGregor equipment, but I didn't want to take any chances." When the time came, Nicklaus was ready to sign with MacGregor. But a flashy entrepreneur named Jack Harkins, president of the First Flight Golf Co., snagged the proceedings. He offered Nicklaus a huge bonus to sign with his firm. Jack wanted to go with MacGregor, but the bonus offer was very substantial. At that, Bob Rickey went to Ted Bensinger for direction. He told his boss that MacGregor didn't have to top Harkins' offer, only match it. Bensinger said, "Don't lose him," and Nicklaus signed on with MacGregor. It was perhaps the best decision Bensinger ever made during his reign with MacGregor. Nicklaus joined MacGregor in late 1961, and very soon after began paying dividends for the company. In 1962, he won the US Open plus two tour events. and soon after the Firestone Tire & Rubber Co. began using a Jack Nicklaus Signature golf ball as a traffic builder in its stores. Over a period of 12 years. more than 15 million were sold. Discounters & Investment Casting

By the late 1960’s, there was a glut of golf clubs on the market. The growth of new players had slowed, in part because golf's traditional pipeline for new players/customers, the caddie, had been largely replaced by golf cars. Besides, the hippie generation was not into golf. As a result, manufacturers of original equipment found themselves with a lot of unsold inventory at the end of every season. The pressure was relieved by the emergence of the off-course golf discount store. These were run by accredited PGA professionals, who bought in large quantities and sold at prices much lower than the pro shop, and even the traditional retail outlets. The discounter prices were so attractive that even members of the best, wealthiest private club were bypassing their home pro for equipment. The manufacturers unloaded on them, making room for the next year's models of clubs. So much for Clarence Rickey's "carriage trade" concept! Secondly, there was a major shift in equipment manufacturing with the development of the investment cast iron. With the lost-wax process, a complete clubhead could be produced in essentially one operation. No broaching or milling was necessary, no expert grinding, none of the many hand operations that were required with traditional forged irons. The most stunning implication of this was that anybody who was at all handy with machinery, and had a few dollars to spare, could design and make a clubhead, put a shaft in it and a grip on it, and open for business. There weren't many of these free-lancers working out of their garages, but one of them -- Karsten Solheim -- would indeed make an impact. Solheim was an engineer in the aviation industry who branched into golf with the evolution of the lost-wax process. His first product was an investment cast putter he called the Ping. From putters he branched into irons. Ping sales point was their perimeter weighting, which featured a hollowed-out back and combined a lower center of gravity, and the gear effect of the bulge and roll on woods. Solheim could knock these clubs out readily, because little or no handwork was needed. MacGregor, based in a classical club design tradition, wasn't in a position to compete – at least immediately. And time was of the essence in the new world of golf manufacture. Brunswick's heavy management infrastructure didn't help matters. Toney's Out, Jack's In

Toney Penna was onto the lost-wax process well before it became a reality. He showed a prototype and explained the process at a 1950s national sales meeting. Penna recalled: "I brought it around to Tony Koegel, the president at the time, but he said, Why get into this when the company was doing fine with the MTs, and everything else?." Even when investment casting began to make real headway, MacGregor resisted because it was bent on retaining golf traditions in design and materials. Tradition is what the company had come to stand for. What's more, the staff tour pros didn't like investment cast irons because it was a harder steel and didn't have the feel they were accustomed to with the softer metal of forged clubs. MacGregor would get into investment casting, of course, but by the time it did, Ping had a large head start. By the mid 1960s, Penna was being eased out of MacGregor. His dictatorial style and improvisational methods didn't fit into the Brunswick modus operandi. He left and started his own company. His first product was an investment cast iron. Tommy Armour had long before left off having any real involvement with MacGregor, and in the mid-1960s accepted an offer to put his name on the PGA-brand clubs. No one from Brunswick missed him. With Clarence Rickey, Penna and Armour gone, MacGregor had lost the nucleus of leadership and ingenuity that made it great. But the brand name was still so potent, and its equipment still so prized, that it enticed a number of up-and-coming young tour pros to sign on. They included Johnny Miller, Tom Watson, Mickey Wright and Tom Weiskopf.

Brunswick Bails Out

Despite the surge Jack Nicklaus gave MacGregor, the total business picture for the company was dim. Many felt the operating overhead incurred at the executive level was eating up the profits. And interest in golf had leveled out after the Arnold Palmer/ President Eisenhower-inspired surge. Also, the Vietnam war was beginning to heat up, causing an inflationary spiral in the nation's economy. In addition, Brunswick upper management was experiencing considerable turnover. Within one eighteen month stretch, MacGregor had five different presidents. The company's golf ball was considerably improved, the quality of the clubs had been restored, and the Nicklaus infusion was very promising. But in the final analysis, the Brunswick corporate style, and now the lack of continuity in the executive branch, spelled big trouble. As a MacGregor man with the firm at the time put it, "You can't run a golf business such as ours in a conventional corporate way. It is too personal a business, especially the golf pro end of it." In 1978, Brunswick began looking for a buyer of its golf division. There was a sense among old-line MacGregorites that if Brunswick couldn't sell MacGregor it would liquidate the "greatest name in golf " But a buyer was found. New OwnersIn 1978, MacGregor was purchased by the Wickes Corporation, a firm that ranked first in retail lumber sales to home builders, and second in retail furniture. It had 280 stores in 37 States. and 65 in Europe. It also owned a chain of drugstores and super-markets (Snyder and Red Owl), a chain of retail clothing stores, and controlled a number of companies manufacturing machinery and processing equipment for the lumber and farm industries. A big company, it was golf related to some extent through its wood-working interests, but more in fact of the executive vice president behind the deal, Clark Johnson. Johnson was a single-digit handicap golfer, and a real golf aficionado. He belonged to La Jolla CC, in San Diego, where Wickes was headquartered, to the famed Pine Valley CC, in New Jersey, and the Royal & Ancient Golf Club of St. Andrews, Scotland. His boss, E.I. McNeely, chairman and CEO of Wickes, was also a golfer, but at first wasn't sure if he should okay the purchase of MacGregor. Johnson convinced him to go forward, but what must have been behind McNeely's reticence was the knowledge that Wickes was getting into financial trouble. It had become overextended with its many acquisitions prior to adding MacGregor to its list, and with the economy on a serious downturn and Wickes' core business slumping, things were not promising. Forced by its bankers to cut back, in April, 1982 Wickes sold MacGregor to Jack Nicklaus and Clark Johnson. Thirty days later, Wickes filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. It was at the time the biggest Chapter 11 filing in corporate American history. Wickes gave MacGregor a good go, installing Jack Curran as president. An accountant by profession, Curran was a hard-nosed businessman who watched the books carefully, and otherwise allowed free rein to those who knew their side of the business. Under Curran, MacGregor got back on track selling clubs and balls, and the tour staff was holding up nicely. In the 1975 Masters, which featured a terrific shoot-out between Nicklaus, Johnny Miller and Tom Weiskopf, the last four players on the course were carrying MacGregor bags--the three named above, plus Tom Watson. After their purchase, Nicklaus and Johnson called their new company Four Square, but of course sold the equipment as MacGregor. Nicklaus was named the president and CEO of what was now a $40 million company. Johnson didn't stay on very long -- leaving in early 1984 -- and was replaced by George Nichols, who had been with Johnston & Murphy's golf shoe division for 20 years, the last five as president. Nichols was also president of the Bostonian golf shoe operation, which is how he came to know Nicklaus. Nichols was effectively put in charge of MacGregor. MacGregor Enters the New Golf Age

The first thing George Nichols did was sell off 75 percent of MacGregor Japanese operation, MacGregor Japan. MacGregor was doing well in Japan, but the profits couldn't be taken out of the country without paving a huge tax. The sale of MacGregor Japan brought Nichols important working capital for his job at home. Nichols' next big move was to bring MacGregor's product line up to date with the high-tech world of golf. Nicklaus and Johnson were golf traditionalists at heart, and resisted the movement in the industry toward "game improvement" clubs featuring investment cast, perimeter-weighted irons, and overall lighter equipment.  MacGregor's Response: The First Oversized Golf Club MacGregor's Response: The First Oversized Golf ClubNichols had inherited Clay Long from the previous MacGregor regime. Long was a tour-quality golfer who decided to forgo that career when an offer from MacGregor came to him in 1980. Long's first project was to design an investment-cast, cavity-back iron. The result was the CG-1800, and it got a big boost when Chi-Chi Rodriguez used it to win a number of tournaments in one year on the PGA Senior Tour. In fact, the CG-1800 was the first oversized iron in the industry, but MacGregor didn't market it as such. The move to oversize came as part of another Long concept--the Response ZT Putter that Jack Nicklaus used to win the 1986 Masters, one of the most dramatic victories in golf history. The original sales forecast for this oversize, high inertia aluminum putter was 6,000 units. This turned into 150,000 units, and eventually over the next three years 350,000. It was the single biggest seller in MacGregor history. With the success of the Response ZT, MacGregor was back in the modern age of club development. Along Comes Titanium

In 1988, the oversize club evolution was well under way and MacGregor had a role in the market place with a variety of models. Now they began looking into how a bigger metalwood could be made light enough, but also strong enough, to withstand the impact with the ball. With the steel being used for the first metalwoods, to keep the overall weight at around 14 ounces (considered the optimum), it meant stretching the metal to get it bigger. This creates a thin clubface susceptible to caving in at impact, which in fact was the case with Callaway's first metalwoods. Long knew about titanium, and thought it was the answer because it was very strong, and also lighter than the metal being used. So it was a question of finding a way to buttress the clubface of a titanium metalwood. Here, Long cashed in on MacGregor long-standing reputation for innovation. Cray Research, the Minnesota-based supercomputer manufacturer, was involved as a corporate sponsor of the 1992 US Open, being played at Hazeltine CC, in Minneapolis. Cray wanted to demonstrate its capabilities in its corporate tent at the Open in a golf-related way, and contacted MacGregor for an idea. Long was working on the problems of titanium, and saw an opportunity. "No one had ever done a finite motion and impact analysis of what happens to a clubhead when it makes contact with the ball." said Long. "Everyone knew the face gave way to some extent, but we thought there was more to it. I asked Cray to do an impact analysis for us. It was something we could never have afforded on our own. The computer time was worth about $2,000 a hour. Cray said they'd supply the computer time, and build a computer model of a metalwood impacting a ball at 100 miles per hour. "Cray showed the results in their tent at Hazeltine. The results turned out to be an incredible piece of information. We saw all the stresses. All of them!" The New with Some Old Strikes AgainIn 1988, MacGregor had another success story melding the old and the new. The JNP iron was oversized, perimeter weighted, and cavity backed, but forged rather than investment cast. There was a growing interest in a softer feel than the investment cast clubs offered, and other clubmakers had been developing equipment along this line. But MacGregor's version had a thinner top line than the others, which was more appealing to better players, and the model made inroads on the marketplace. Nicklaus Eases Out of MacGregorGeorge Nichols' plan to revive MacGregor's fortunes worked. The company had come back to profitability, and was retaining its panache as a high-tech and classic club maker. However, Jack Nicklaus had a number of other business interests that were taking a good bit of his time, in particular his golf course architecture, and he had run into some serious legal and financial difficulties in respect to a golf course project he was involved in around the New York City area. He was unable to further finance MacGregor, and the company was sold to Amer Group Ltd., a Finnish holding company. Amer had extensive tobacco interests, but also had been in sporting goods (mainly related to skiing). Amer bought 80 percent of MacGregor, with Nicklaus holding the remaining 20 percent. George Nichols left MacGregor, his position taken by a number of different men over the next few years. As in past regimes, instability at the top of the executive ladder hampered MacGregor's progress. Things became more difficult when Nicklaus decided he no longer wanted clubs with his name on them analogous with retail stores. Since the 1960s, the Jack Nicklaus Signature and Golden Bear brands had sold very well at retail, but Nicklaus now wanted to be associated with the "premium" equipment sold only through green-grass outlets. In a word, he wanted only Clarence Rickey's "carriage trade." Amer Group was not happy with this -- its considerable investment and the overhead of a big plant producing a large volume of equipment was predicated on the volume of sales Nicklaus generated in the retail stores. Nicklaus was insistent on this new direction; Amer Group disagreed, and there was a parting of the ways. Nicklaus sold his remaining interest in MacGregor to Amer Group in 1991. Amer Group then brought in Dave Gibbons to lead MacGregor. Gibbons had been with Wilson Sporting Goods for 14 years, and was familiar to Amer, which had also bought Wilson around the same time it bought MacGregor. In the six years that Amer Group managed MacGregor, the equipment that was developed and marketed continued to have the classic MacGregor lines, with some adaptations to increase appeal to the average golfer. In short, the MacGregor look was married to game improvement features such as off-set hosels, perimeter weighting, longer and lighter clubs, etc. But it wasn't only the average golfer who benefited. The history of MacGregor Golf, through all its trials and tribulations, is a remarkable story -- with dramatic highs and lows. Throughout, the company has managed to maintain the special quality of the products that have set it apart for over 100 years. And plans are well underway for MacGregor's next hundred years. The MacGregor History TimeLine

1829 -- The Crawford Brothers found the Dayton Shoe Last Company, in Dayton, Ohio, the forerunner of MacGregor Golf.

1886 -- Edward Canby and John McGregor become partners in the Dayton Shoe Last Co., which is renamed Crawford, McGregor & Canby, the name by which MacGregor Golf operated until 1936.

1897 -- Crawford, McGregor & Canby (CMC) becomes the second American manufacturer of golf equipment, after Spalding.

1889 -- Famous Scottish professional, Willie Dunn, is hired as CMC (MacGregor) professional advisor, club designer, and celebrity pro staffer.

1900 -- CMC ships 100,000 machine-turned persimmon clubheads to British equipment manufacturers.

1900 -- CMC originates the golf store concept. shops within downtown department stores of major cities as a way to reach more golfers.

1901-2 -- CMC licenses from the inventor the right to make its clubs with the shaft inserted into the socket of the neck or hosel of the head, rather than splicing it to the outside. CMC is the first American equipment maker to produce its clubs this way. Soon, all manufacturers follow suit.

1912-13 -- CMC hires Will Sime, the noted Scots golf club designer, as its chief club designer.

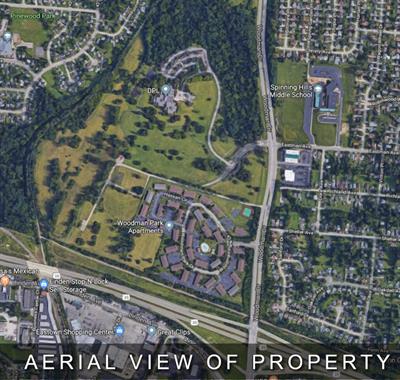

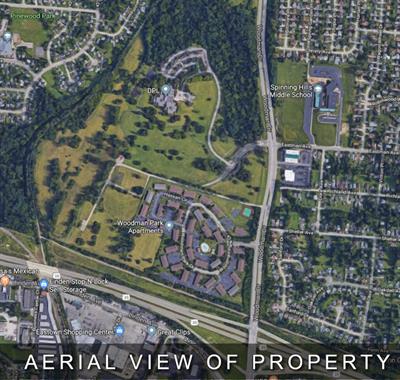

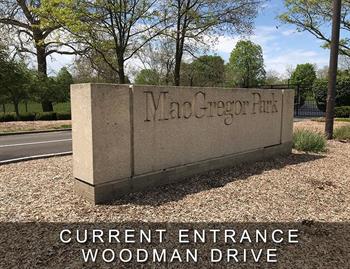

1917 -- CMC/MacGregor starts to builds the first company golf course, in Dayton, for use by its employees, and as a testing ground for its equipment. Construction by Obie O'Bannon 1921 -- Sime's first major contribution to CMC MacGregor's line is the "Bap" driver and brassie, a redesign of wooden clubheads into a more compact shape. The idea is taken from biscuits Sime's mother baked at home, called baps. The "Bap" design effectively changes the essential configuration of wood clubs, as it is followed by all other manufacturers. 1922 -- MacGregor Golf Course Opens (Many of you may remember the DP & L Course, the Property is Now MacGregor Park) 1922 -- CMC/MacGregor is the first equipment manufacturer to offer clubs with the new steel shaft.

1924 -- CMC/MacGregor develops the "Neutralizer," a wooden dowel inserted in the steel shaft to dampen vibration when a ball is hit. 1928 -- CMC/MacGregor introduces "Macoid", a celluloid the company developed for steel shafts to prevent rusting. 1931-93 -- In this 62-year period MacGregor staff tour pros win 18 PGA Championships, 17 Masters, 16 US Opens, seven British Opens; ten MacGregor pros lead the annual money-winning list, and eight win the Vardon Trophy. 1932 -- The Great Depression takes its toll on CMC/MacGregor, which has to halve its work force. 1934 -- CMC/MacGregor considers filing for bankruptcy. Edward Canby hires a management consulting firm to put MacGregor in condition for sale. 1936 -- CMC/MacGregor sold to P. Goldsmith Sons, a Cincinnati-based sporting -goods manufacturer. Clarence Rickey named president of the golf division. Rickey brings in Tommy Armour as the head of a professional advisory staff. A line of Armour clubs is put in the works. Rickey also hires Toney Penna as advance man contacting club pros, and to scout tour pros as potential CMC/MacGregor staff players. Clarence Rickey declares that the golf division will now be known as the MacGregor Golf Co. 1937-39 -- Tommy Armour plays major role in redesign of MacGregor woods, eschewing the blocky Bap shape for a sleeker look that becomes the standard in the industry. Armour is also behind the development of the bulge-and-roll clubface for woods, which also becomes a standard in the industry. MacGregor signs Jimmy Demaret, Byron Nelson and Ben Hogan to its professional advisory staff for a total of $5,000. Two weeks after Nelson signs on, he wins the U.S. Open (1939) with a set of Armour irons he took off the rack in Armour's Boca Raton pro shop. 1941-45 -- During World War II, golf equipment manufacture was deemed non-essential. Steel, rubber and other essential materials were unavailable. For the duration, MacGregor managed to keep afloat by taking in used golf balls for re-covering. The compant also manufactured camouflage clothing, airplane safety belts, GI luggage, survival kits, and sportswear (shirts, sweaters, rain jackets). 1945 -- Clarence Rickey, age 47, is killed in an automobile accident while making sales calls. 1946 -- MacGregor begins to produce its own golf ball; stops contracting the work out to the Worthington Golf Ball Co. 1946-49 -- MacGregor sets full-scale into the manufacture and distribution of a line of golf clothing. This brings about a conflict with McGregor-Doniger, an already well established clothing manufacturer. In 1948, MacGregor Golf agreed not to sell any clothing, under any name, and McGregor-Doniger agreed never to make and sell golf equipment. MacGregor moves from Dayton to much larger quarters in Cincinnati. MacGregor designs first broaching machine for milling the backs of iron clubheads, which saves considerable money and space. 1950-55 -- Toney Penna becomes chief designer for MacGregor Golf. His first product is the MT iron, which proves to be extremely successful. It incorporates the lower-center of-gravity concept for the first time in the industry. Penna follows this success up with a number of different products. He introduces the Colorkrom MT iron, with a bronze-colored hitting area, the black-faced FC (for flame ceramic)-4000 iron, which uses jet and rocket industry metallurgy ideas-. brightly colored golf bags; the two-tone "Eye-O-Matic" insert for woods; the "Double-Duty" wedge, for sand and grass play. 1956 -- MacGregor Golf claims close to 30 percent of the private club pro shop business, the result of Clarence Rickey's plan to make MacGregor supplier of equipment to golfs "carriage trade." 1958 -- The Goldsmiths sell MacGregor Golf to Brunswick-Balke-Colender, a leading manufacturer of bowling equipment. 1961 -- Jack Nicklaus signs on to play MacGregor equipment. 1962 -- MacGregor plant moved from Cincinnati to Albany, Georgia. Tommy Armour leaves MacGregor. 1963 -- Toney Penna leaves MacGregor to start up his own equipment manufacturing firm. 1978 -- Brunswick sells MacGregor Golf to the Wickes Companies. 1979 -- Robert D. Rickey Writes the History of MacGregor (1829 to 1979) 1982 -- Wickes sells MacGregor to Jack Nicklaus and Clark Johnson. 1984 -- Clark Johnson leaves MacGregor Golf. He is replaced by George Nichols, who assumes role of president and CEO. Nichols brings MacGregor into line with the industry by introducing a light weight steel shaft and begins developing perimeter-weighted, investment cast irons and metalwoods. At the same time MacGregor recalls golf's older tradition by introducing the Jack Nicklaus Limited Edition irons and woods. Each of the 1,000 sets was promptly sold for $2,500 a set. 1986 -- Amer Group, a Finnish holding company, buys 80 percent of MacGregor Golf from Jack Nicklaus, who retains the remaining 20 percent. George Nichols leaves MacGregor.

1986-7 -- Clay Long, MacGregor's club designer and head of research and development, develops MacGregor's first investment-cast, cavity-back, and the industry's first oversize iron, the CG-1800. Chi-Chi Rodriguez wins seven tournaments on the Senior PGA Tour using the clubs, including the PGA Seniors Championship. The model sells well. Long also develops the oversize Response ZT putter. Jack Nicklaus uses it to win the 1986 Masters. MacGrecor sells 150,000 of the putters in the year following the victory by Nicklaus, 350,000 over the next three years. The club also touches off the oversized club revolution in the industry.

1988 -- MacGregor makes the first use of titanium with the introduction of the T-920 oversized metalwood.

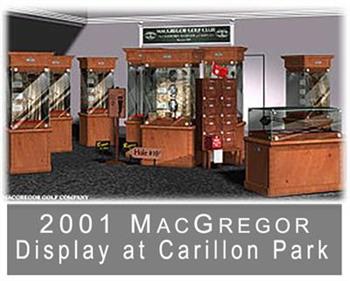

1990 -- Jack Nicklaus sells his 20 percent interest in MacGregor to Amer Group.